The overall objective of SmartPhones4Water’s work in the Kathmandu Valley is to assist with generating the data required to guide water management decisions and allow for wise stewardship of water resources, and it has a rather long time scale associated with it. You need continuous data over an extensive period of time to understand how available water supplies are changing and to pick up on trends and respond accordingly. For example, in the United States, many of the data records regarding stage and flow in streams and rivers, and water levels in groundwater wells, go back around a hundred years into the early 20th century. This lengthy data record allows water managers and policy makers to better understand how factors such as increasing urbanization, changes in agricultural practices and land use, and climate change affect water resources. We are just beginning to generate and collect these data in the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal with all of our local project partners, but we know that over time, as the length of the data records grow, the value of the data records grow as well.

However, after that lengthy aside as an introduction, this month’s story is about how the data we are collecting can also be immediately useful and positively impact the lives of people. There may be some additional follow-up stories on this same topic (as there is a lot to explore and a lot to say), but this will serve as an introduction to the flow measurement data we are collecting at stone spouts scattered across the Kathmandu Valley.

Stone Spouts

Stone spouts (known as dhungadhara by phonetically-spelling Nepali words in English, or as ढुङ्गे धारा for those who can read Nepali) serve as communal water sources for people living in the Kathmandu Valley. They are locations where the groundwater system naturally discharges into a spring or surface water body (e.g. underground water appears on the surface). Many of these have been developed and the discharge points have been channeled into these ‘stone spouts’ to aid in water collection and usage. People, especially the poor and underprivileged, come here to collect water for use in their homes, to do laundry, to bathe, etc.

As we’ve mentioned in a previous story, the population in the Kathmandu Valley has drastically increased over the last 50 years or so. This has put great stress on the water resources of the valley and is one of the reasons that we chose this location for our initial pilot project. For those who can afford to drill and operate wells, groundwater provides a consistent, reliable supply of water. However, as groundwater extractions in the valley increase, groundwater levels decline (we’re targeting groundwater level data collection as another component of our project). Consistent groundwater level decline can result in various negative impacts on both people and the environment.

Since we’re scientists and engineers (i.e. nerds, or enginerds, as some of us like to say), we like reading, because we actually think reading is fun and because we learn stuff by doing it. In case you feel similarly, there’s a great paper that was published by Charles Theis in 1940 that explains how pumping groundwater affects surface water (the USGS has a summary of it available here). Basically, all water discharged from a well represents a loss of water somewhere else. Typically this process starts as a loss of water storage in the underground aquifer that the well is tapped into. However, with sufficient pumping over time, that resulting loss of water can present itself as reduced flow in streams and rivers, or reduced flow at springs such as the stone spouts in the Kathmandu Valley. Reduced flow is our main concern at these stone spout locations, especially since they serve as the primary water source for many of the poor and underprivileged (i.e. those who don’t have access to water from a well or could not afford to pay for water pumped from a well should the stone spouts dry up).

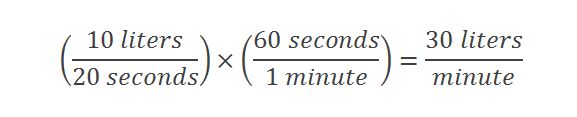

The flow measurement data collection the S4W staff completes at these stone spout locations is very simple, but also very effective. We utilize the same SmartPhone app that we use to record precipitation data (find out more about how it works here), but for this application we are measuring a volumetric flow rate. All that you need to record the flow rate at these locations is a bucket of known volume and a stop watch timer (a feature that basically all SmartPhones have). The bucket is held under the stone spout, the timer is started, and the time it takes to fill up the bucket is recorded, and voila, you’ve measured the flow rate. For example, if you have a ten liter bucket and it takes 20 seconds to fill up, the flow rate (as measured in liters per minute) would be:

We’ve included a photo of a staff member performing one of these measurements below, recording the volume of caught over a certain amount of time.

The data that we have already collected at stone spout locations helps define existing conditions, and continuing data collection will show any changes (once again, with the main concern being decreases in flow) that occur over time. These stone spout locations are critical communal water sources that especially the poor and underprivileged are dependent on; if they are affected, people in these communities may find themselves without access to water, one of the most basic needs that people have.

If you’re interested, you can read another article about the stone spouts in the Kathmandu Valley here.